Though some Christians may pretend that conservative religious faith has remained somewhat constant through the centuries, what even the most conservative literalist believes today varies in significant ways from the world view of the early church. As late as the 1500s, it was assumed that angels and demons controlled the most mundane aspects of life. The vast territory that we now call the natural world did not exist in the minds of most people until very recently. Christian Europe believed that demonic forces directly and regularly caused things like illness, death, wasting of crops, barrenness, etc. that are now understood to have more "natural" causes.

This mindset lives on today. As quoted in the Times of India, "Officials at Nepal's state-run airline have sacrificed two goats to appease Akash Bhairab, the Hindu sky god, following technical problems with one of its Boeing 757 aircraft, the carrier said on Tuesday."

This is not to say that religion is unimportant. One of the themes I have been trying to develop on this blog is that we need to come to new understandings about the interplay of science and religion. Belief is bound up in what it means to be human, it would seem. Faith is an integral part of how we go about our lives. At the same time, much of our traditional religious frameworks are bound up in cosmologies and understandings of cause and effect that we no longer share with our spiritual fore bearers. We have a largely naturalistic view of the world, but our spiritual framework is defined by people who saw even the most mundane occurrences as fraught with supernatural agency.

Rather than argue that faith requires us to believe absurd things, we need to work out how to maintain faith in light of the massive shift in worldview that has overtaken us as the result of our study of the natural world.

Wednesday, December 26, 2007

Friday, December 14, 2007

We've Already Moved Past Biblical Literalism

If you believe the earth rotates the sun, then you believe things that science has discovered that contradicts the bible. Do you extend your faith to a flat earth and a sun that moves across the sky?

In fact, you have changed the way you read the Bible such that you don't even think the Bible teaches that. The fact that Martin Luther thought that it did shows that it our interpretation that has changed, and not the Bible's teaching.

Science assumes naturalism because that is all it can study. It is like the old joke about a drunk looking under a streetlight for his car keys because the light is better there. Science assumes naturalism, not as a commitment to atheism, but because it won't work when the answer is "God did it."

This is where the gaps of the "God in the Gaps" theology comes from. When science can't find an answer, you can assume that we'll never figure it out, we might figure it out, or that God did it. Progress is only made in science when you assume that we might be able to fougre it out. Unexpectedly perhaps, this assumption has been so successful, there has been no reason to question it.

The big bang did happen. This is not speculation, it is based on evidence, and confirmed by experiment. The earth is not 6,000 years old - this is based on evidence, and confirmed by experiment. So it is hardly fair or accurate to say that these are two competeing views of the how we got here. A fair and balanced treatment of evolution would say that evolution is the only theory that explains the facts. Full stop.

The idea of the Big Bang is weird, no doubt. And you can believe that God did it, no doubt. But what God did not do is create the earth 6,000 years ago. What God did not do is create species from the mud, just as they are (or even mostly as they are) today. Just like a flat earth and a sun that is drug across the sky, modern discoveries give us challenges in reading the Bible. These are real challenges, but they should not be papered over by denying the age of the earth and the actions of evolution.

Sunday, December 09, 2007

Biblical Faith and Confidence in The Natural World

The level of comfort I have with evolution and other scientific explanations of the world and how it works is pretty high. But I do not call that confidence faith.

"Now faith is being sure of what we hope for and certain of what we do not see." (Hebrews 11:1) I do not have faith that gravity is at work. I do not need to hope that gravity shows up and does its thing, nor are its effects unseen. Evolution is the same - its effects are everywhere, and the evidence for evolution is everywhere.

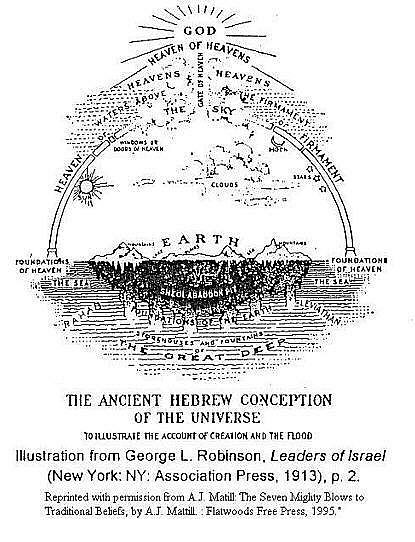

One problem a Biblical faith must address is that a plain reading of the Bible lays out a world that was created 6,000 years ago and suffered a world-wide flood 4,500 years ago. Where all living creatures were within walking distance of the ark. A world where stopping the sun will lengthen the day and where Jesus went up into the sky to reach heaven, and was to return from the sky before his followers died. This is a book with two different creation accounts, two different 10 commandments, and irreconcilable differences in the chronology and activities of Jesus' life on earth.

These things are simply true about the Bible, and just like the fact of evolution, should in all honesty be faced. Some biblical literalists tell us that rather than face these facts, the facts should be denied, and if they can't be denied, that a Christian is supposed to make a virtue of believing things that are obviously not true (they call this faith - compare this with Hebrews 11:1 above, and you'll see that this is an innovation, and shares little with the notion of Biblical faith).

As a personal religion, I am OK with that (well, it makes me uncomfortable, but we all believe things that aren't true). I put these beliefs in the same category as astrology and palm reading.

What has me concerned is that there are now enough of these folks who believe that ignorance is a virtue that they are being successful in rolling back confidence in science. Educators are being fired for doing their jobs, teachers are being pressured to skip over the teaching of evolution, and pastors are pandering to this "appearance of godliness" by blaming the teaching of evolution for the world's ills.

It is important to live in the light as much as possible, in part because we risk making grave errors when we base our public and private lives on a lie. It is difficult work to figure out how to read the Bible in light of what we have learned about the natural world. But just like we managed to adjust our thinking about the Bible to Galileo's revelations, we can adjust to reading the Bible in light of what we've learned about the world via evolution and quantum mechanics.

"Now faith is being sure of what we hope for and certain of what we do not see." (Hebrews 11:1) I do not have faith that gravity is at work. I do not need to hope that gravity shows up and does its thing, nor are its effects unseen. Evolution is the same - its effects are everywhere, and the evidence for evolution is everywhere.

One problem a Biblical faith must address is that a plain reading of the Bible lays out a world that was created 6,000 years ago and suffered a world-wide flood 4,500 years ago. Where all living creatures were within walking distance of the ark. A world where stopping the sun will lengthen the day and where Jesus went up into the sky to reach heaven, and was to return from the sky before his followers died. This is a book with two different creation accounts, two different 10 commandments, and irreconcilable differences in the chronology and activities of Jesus' life on earth.

These things are simply true about the Bible, and just like the fact of evolution, should in all honesty be faced. Some biblical literalists tell us that rather than face these facts, the facts should be denied, and if they can't be denied, that a Christian is supposed to make a virtue of believing things that are obviously not true (they call this faith - compare this with Hebrews 11:1 above, and you'll see that this is an innovation, and shares little with the notion of Biblical faith).

As a personal religion, I am OK with that (well, it makes me uncomfortable, but we all believe things that aren't true). I put these beliefs in the same category as astrology and palm reading.

What has me concerned is that there are now enough of these folks who believe that ignorance is a virtue that they are being successful in rolling back confidence in science. Educators are being fired for doing their jobs, teachers are being pressured to skip over the teaching of evolution, and pastors are pandering to this "appearance of godliness" by blaming the teaching of evolution for the world's ills.

It is important to live in the light as much as possible, in part because we risk making grave errors when we base our public and private lives on a lie. It is difficult work to figure out how to read the Bible in light of what we have learned about the natural world. But just like we managed to adjust our thinking about the Bible to Galileo's revelations, we can adjust to reading the Bible in light of what we've learned about the world via evolution and quantum mechanics.

Monday, November 26, 2007

Faith: Science and Religion

Science and religion use the word faith in two very different ways. Speaking of faith as it relates to the expectation that the earth will rotate around to face the sun again tomorrow is quite different than the faith praised in Hebrews 11 ("Now faith is being sure of what we hope for and certain of what we do not see"). To suggest that science is also based on faith, because some of the foundational laws of physics are not experimentally demonstrated but treated as "givens," is misleading.

True, Carl Popper (the influential philosopher of science) noted that the financial disclaimer "Past performance is no guarantee of future returns" is also true of inductive reasoning. But, just like investors view past performance as an indicator of future returns, many regard Popper's critique of induction as a kind of reductio ad absurdum argument - we have good reason to expect natural laws to remain in effect. Just because we can't be absolutely certain does not mean that we have no certainty at all. We go with successful investment funds because we expect the future to look like the past. Unlike funds, however, we so far have found no exceptions to the rule that the present continues to look like the past, as far as the laws of physics go - and so it is reasonable to expect the future to look like the past as well. This is a far cry from the Biblical notion of faith.

The Bible commends faith that holds firm in the absence of evidence. Good science encourage faith (if that is the right world at all) only in the face of compelling (even if not irrefutable) evidence.

Science is just an extension of careful observation and reasoning. We've been doing science for thousands of years. What enabled what we think of as modern science to transform the world's culture in a few hundred years seems to be a combination of the right political climate and a rejection of traditional explanations ("As above, so below"). That, and methodological naturalism.

Taken from this perspective, science and faith don't present any more of a conflict than did faith and the natural world for the author of Hebrews. The attempt to make science just another faith (and a religion on top of that) looks to me to be an attempt at undercutting the demand for faith. The author of Hebrews argues not that science is just as uncertain as religion, but that we have faith in the face of uncertainty. Rather than tear down science, Hebrews urges, build up faith.

True, Carl Popper (the influential philosopher of science) noted that the financial disclaimer "Past performance is no guarantee of future returns" is also true of inductive reasoning. But, just like investors view past performance as an indicator of future returns, many regard Popper's critique of induction as a kind of reductio ad absurdum argument - we have good reason to expect natural laws to remain in effect. Just because we can't be absolutely certain does not mean that we have no certainty at all. We go with successful investment funds because we expect the future to look like the past. Unlike funds, however, we so far have found no exceptions to the rule that the present continues to look like the past, as far as the laws of physics go - and so it is reasonable to expect the future to look like the past as well. This is a far cry from the Biblical notion of faith.

The Bible commends faith that holds firm in the absence of evidence. Good science encourage faith (if that is the right world at all) only in the face of compelling (even if not irrefutable) evidence.

Science is just an extension of careful observation and reasoning. We've been doing science for thousands of years. What enabled what we think of as modern science to transform the world's culture in a few hundred years seems to be a combination of the right political climate and a rejection of traditional explanations ("As above, so below"). That, and methodological naturalism.

Taken from this perspective, science and faith don't present any more of a conflict than did faith and the natural world for the author of Hebrews. The attempt to make science just another faith (and a religion on top of that) looks to me to be an attempt at undercutting the demand for faith. The author of Hebrews argues not that science is just as uncertain as religion, but that we have faith in the face of uncertainty. Rather than tear down science, Hebrews urges, build up faith.

Tuesday, November 20, 2007

Does Science Hate God?

Some creationists think that Douglas Futuyma provides a "smoking gun," proving a scientific bias against their faith, when he says:

"Evolutionary theory does not admit conscious anticipation of the future (i.e. conscious forethought)."

Futuyma seems to be saying that the theory of evolution has no room for the idea of guided processes - because, as in the rest of scientific explanations discovered to date, the world "works" - things have been successfully explained without resorting to "and then a miracle occurs." To say that evolution works without guidance is to say that it is a natural process, which does not require the intervention of God.

This is, in fact, a true statement about EVERYTHING that science discovers. Every scientific theory deserves the same criticism (God's intervention is not required). Think about this for a moment. This represents a sea-change in how people think about the world. So far, NO process identified to date requires the intervention of a deity to explain what goes on. Not the sun rise, thunder and lightening, crops, birth, death, the creation of the sun, moon, stars or earth. This is not what scientists expected when Western science got started in earnest, just a few hundred years ago.

If this is true (and it is), then why single evolution out for explicit criticism? I suspect because it runs afoul of the way some Christians (biblical literalists) interpret Genesis 1 and 2. If God did not fashion Adam from the mud some 6,000 years ago, then Jesus did not die for our sins (or so their argument goes). Millions of Christian do not share their perspective, but this does not matter to the literalists. It is their way or to Hell with you. What is more, the rest of science will get its turn. Chemistry, geology, cosmology - not to mention anthropology, archeology, history - the list goes on - will have to be heavily "edited" if the goal is conformity with biblical literalism. This is just another reason to resist the ongoing attempt to censor science in the name of piety. You may not care about the theory of evolution, but when they get around to something you do care about, it will be too late.

Of course science has implications for theology. If you believe that God rides a chariot across the sky, pulling the sun, you are in trouble (unless you believe in an invisible chariot, I guess). So, yes, evolution suggests that things happen in a particular way (using natural processes, not requiring God’s direct intervention). You can look at how the world works and see no God, you can see God as the creator, using natural processes to accomplish his purposes, or you can argue for the suppression of science because you disagree with its conclusion.

"Evolutionary theory does not admit conscious anticipation of the future (i.e. conscious forethought)."

Futuyma seems to be saying that the theory of evolution has no room for the idea of guided processes - because, as in the rest of scientific explanations discovered to date, the world "works" - things have been successfully explained without resorting to "and then a miracle occurs." To say that evolution works without guidance is to say that it is a natural process, which does not require the intervention of God.

This is, in fact, a true statement about EVERYTHING that science discovers. Every scientific theory deserves the same criticism (God's intervention is not required). Think about this for a moment. This represents a sea-change in how people think about the world. So far, NO process identified to date requires the intervention of a deity to explain what goes on. Not the sun rise, thunder and lightening, crops, birth, death, the creation of the sun, moon, stars or earth. This is not what scientists expected when Western science got started in earnest, just a few hundred years ago.

If this is true (and it is), then why single evolution out for explicit criticism? I suspect because it runs afoul of the way some Christians (biblical literalists) interpret Genesis 1 and 2. If God did not fashion Adam from the mud some 6,000 years ago, then Jesus did not die for our sins (or so their argument goes). Millions of Christian do not share their perspective, but this does not matter to the literalists. It is their way or to Hell with you. What is more, the rest of science will get its turn. Chemistry, geology, cosmology - not to mention anthropology, archeology, history - the list goes on - will have to be heavily "edited" if the goal is conformity with biblical literalism. This is just another reason to resist the ongoing attempt to censor science in the name of piety. You may not care about the theory of evolution, but when they get around to something you do care about, it will be too late.

Of course science has implications for theology. If you believe that God rides a chariot across the sky, pulling the sun, you are in trouble (unless you believe in an invisible chariot, I guess). So, yes, evolution suggests that things happen in a particular way (using natural processes, not requiring God’s direct intervention). You can look at how the world works and see no God, you can see God as the creator, using natural processes to accomplish his purposes, or you can argue for the suppression of science because you disagree with its conclusion.

Biblicalism: Addressing the Shortfalls of Methodological Naturalism

Senator Brownback is on recording as advocating that we should just say no to scientific ideas that contradict conservative Christian theology. This is an idea that has far-reaching implications.

Let me flesh out the proposal - let's call it Biblicalism. The way Biblicalism proceeds in discovering how things work is: 1) identify all statements from the Bible that contain information about the natural world, and 2) set those down in a "Foundations of Science" textbook as "Givens." This would include the Bible's statements on cosmology, geology, chemistry, physics, biology, history, archeology, etc.

An "idea review board" would be set up, manned by Bible Scholars (only men, and members would be picked by a "literal-off", in which those who can explain how the most number of passages in the Bible are meant to be taken literally (exactly as written in the KJV) would be chosen). Any evidence that contradicts these Givens would be rejected. All explanations that do not fit with these Givens are rejected. Anyone who insisted in arguing for things that contradicts the Givens would be prohibited from publishing or teaching (otherwise, it just gets too messy, as the discussions over creation and evolution have shown).

You'd need to add some a new scientific discipline: Supernatural influence (giving input to other disciplines about how spiritual forces are impacting politics, morals, weather, geological processes like earthquakes and volcanoes, fashion, etc). They would also add steps to ostensibly "natural" processes to highlight God's part. For example, since "in Him we move, and breathe, and have our being" we'd need to add God's part to the study of pulmonology). We might want to consider banning mechanical ventilators, for example, because that is clearly breathing when God is no longer helping out. Those liberals who think the passage quoted is poetical must not be allowed to insinuate their materialistic philosophy into innocent minds; that way leads to madness!

You'd need fact checkers to identify when things are attributed to natural causes when in fact there are Givens at work. These errors would have to be corrected, and the violators punished. Sanctions are required, because most Givens will not actually improve the usefulness of the explanation (in fact, they will usually make them less accurate and useful, though more True), so people won't use them unless it is required.

Dispensation will have to be given for engineers to use approaches that contradict the Givens, because otherwise, they won't be able to actually make things work (for example, you'd need a non-Flood geology model to find oil and gas). This is probably best kept quiet, so perhaps we could develop guilds, with strict membership and secrecy requirements.

It would be best to restrict literacy and education in general, as it is a demonstrated fact that education leads to disputation of Givens. For example, in many conservative Christian circles, Seminaries are called "Cemeteries" because a graduate education the Bible leads so many students away from faith in the Givens.

I think that these modest proposals will solve most of the mistakes evident in modern science, and end attacks on the Bible.

Let me flesh out the proposal - let's call it Biblicalism. The way Biblicalism proceeds in discovering how things work is: 1) identify all statements from the Bible that contain information about the natural world, and 2) set those down in a "Foundations of Science" textbook as "Givens." This would include the Bible's statements on cosmology, geology, chemistry, physics, biology, history, archeology, etc.

An "idea review board" would be set up, manned by Bible Scholars (only men, and members would be picked by a "literal-off", in which those who can explain how the most number of passages in the Bible are meant to be taken literally (exactly as written in the KJV) would be chosen). Any evidence that contradicts these Givens would be rejected. All explanations that do not fit with these Givens are rejected. Anyone who insisted in arguing for things that contradicts the Givens would be prohibited from publishing or teaching (otherwise, it just gets too messy, as the discussions over creation and evolution have shown).

You'd need to add some a new scientific discipline: Supernatural influence (giving input to other disciplines about how spiritual forces are impacting politics, morals, weather, geological processes like earthquakes and volcanoes, fashion, etc). They would also add steps to ostensibly "natural" processes to highlight God's part. For example, since "in Him we move, and breathe, and have our being" we'd need to add God's part to the study of pulmonology). We might want to consider banning mechanical ventilators, for example, because that is clearly breathing when God is no longer helping out. Those liberals who think the passage quoted is poetical must not be allowed to insinuate their materialistic philosophy into innocent minds; that way leads to madness!

You'd need fact checkers to identify when things are attributed to natural causes when in fact there are Givens at work. These errors would have to be corrected, and the violators punished. Sanctions are required, because most Givens will not actually improve the usefulness of the explanation (in fact, they will usually make them less accurate and useful, though more True), so people won't use them unless it is required.

Dispensation will have to be given for engineers to use approaches that contradict the Givens, because otherwise, they won't be able to actually make things work (for example, you'd need a non-Flood geology model to find oil and gas). This is probably best kept quiet, so perhaps we could develop guilds, with strict membership and secrecy requirements.

It would be best to restrict literacy and education in general, as it is a demonstrated fact that education leads to disputation of Givens. For example, in many conservative Christian circles, Seminaries are called "Cemeteries" because a graduate education the Bible leads so many students away from faith in the Givens.

I think that these modest proposals will solve most of the mistakes evident in modern science, and end attacks on the Bible.

Saturday, November 17, 2007

Is God outside the universe? Is God the same as the universe?

These days, God is imagined to exist in some other dimension - not bound to this universe. Or conversely, like Gaia, to be the earth, or the universe itself.

I can't imagine how we can know if God exists beyond our universe; we run into a descriptive wall when there is no natural world to think about. What category do we have for what would be "outside" the universe (if such a term means anything)? Revelation does not help us much, because the folks to whom it came had such a different cosmology from ours. Since God has to speak through and into a particular culture (ones lacking the language of physics and modern cosmology), these kind of distinctions don't even come up. It is not at all clear to me that the expansive language used to describe God's remoteness and otherness means non-material or non-local.

To say that God IS all the processes and systems of the universe would make God irrelevant, because to explain the natural world (as science is in process of doing) would also describe God and all her activities. To say that God chooses to act in exact synchronicity with natural law means that we can drop God from the equation. At this point, God becomes an idea, perhaps an inspiring thought - this concept fits few notions of God.

In a similar way, saying that God is supernatural would mean that God is unable to interact with the natural world at all, since so far, we have not detected any uncaused action. That is what supernatural would look like, right? Some physical process taking place with no cause acting on it, or through it - like a vase floating from point a to b though the air, with no possible explanation of how it is happening. So at the very least, God inhabits the universe, without simply being the universe. Inhabiting the universe gives the mechanism of action, and not simply being the universe gives the possibility that God is more than another way of saying natural processes.

What about the millions (billions?) of people who say that they have experienced God just that way? A direct-to-brain sense of God speaking to them (figurative or literal), an experience of comfort and assurance, miraculous coincidence, healings, interventions, appearances of angels at just the right time, just the right word from a friend or a stranger, knowledge of the private thoughts of another person, or predictions of future events that turn out just as described? The difficulty is that these experiences don't seem to stand up to scrutiny; that is, they don't seem to have a statistically significant impact on health, longevity, divorce rate, standard of living (if God blesses His own) and so on. Why do we experience significant spiritual events if they don't seem to impact the overall experience of life on earth? For example, Pat Robertson is a world-famous faith healer, yet he is seeking our Western medicine for his prostate cancer. Is it just me, or is this odd? Millions of people are praying for him, yet his disease is progressing in complete accord with statistical norms. Why this disconnect between what we believe, and what seems to be the case?

We don't perceive reality directly (one simple example: objects don't have color, right? Color is literally in the mind - a way we process the eye's reception of various wavelengths of light bouncing off an object - or so we explain it to ourselves). If I read the popular physics books correctly, all of time already exists, and for some reason we don't understand, we are forced to experience it one "slice" at a time, and only in one direction. There are other examples that suggest that we experience only a small subset of what there is, and that experience is heavily structured and mediated (and sometimes even manufactured) by our sensory and cognitive apparatus.

I am not trying to suggest some "gap" in our understanding is where God is. I am trying to suggest that we are heavily invested in our experience of the world, and even things we are confident about (a blue sky day, for example) represent a heavily coded representation of reality, and not reality itself. We pay attention to the things our brain generates based on data from our five senses because that is what we've got. In this sense, we are like the drunk looking for his keys under the streetlight "because the light is better." Our brain looks for patterns (and finds them). Our brain generates explanations for cognitive dissonance (and we believe them, even when they are patently false). We do better with an optimistic outlook, and our brain paints a rosy picture for us (many of us, some of the time).

I don't think that this means we do not know or experience reality (but we are working under some heavy disadvantages). Much of what we know (and we can easily sort truth from fiction here) is grounded in an actual physical system. That we experience those systems at a remove is a truism we skip for the sake of convenience. So to say that the sky is blue is a shorthand way of saying that receptors in our eyes have registered photons in the 475 nm range, and which our brains are mapping as the color blue (or near enough - if the exact process ends up being different, it won't impact this argument). That synesthesia - experiencing color as smell or taste is a clue that this binding is arbitrary (through hard-wired in the brain); but it does not mean that our description of the sky is any less real.

This is one of the reasons that science has been so successful. By challenging assumptions, insisting on data to support ab assertion, carefully running experiments and having others check the results, by having lots of smart people try to disprove an idea (as opposed to apologetics - having those same smart people rationalize why an idea is correct), we are moving in a more "truthlike" direction as regards our understanding of the natural world.

I know that I personally locate the experience of Spirit in my sense of flow, of synchronicity, of connectedness, of things coming together for a purpose. Perhaps I mean grace. I do not understand why so many people's lives appear to lack that grace. The truly wretched state of billions is the strongest argument against grace that I know - and yet, I still believe I experience it, and witness its effects in the world.

I can't imagine how we can know if God exists beyond our universe; we run into a descriptive wall when there is no natural world to think about. What category do we have for what would be "outside" the universe (if such a term means anything)? Revelation does not help us much, because the folks to whom it came had such a different cosmology from ours. Since God has to speak through and into a particular culture (ones lacking the language of physics and modern cosmology), these kind of distinctions don't even come up. It is not at all clear to me that the expansive language used to describe God's remoteness and otherness means non-material or non-local.

To say that God IS all the processes and systems of the universe would make God irrelevant, because to explain the natural world (as science is in process of doing) would also describe God and all her activities. To say that God chooses to act in exact synchronicity with natural law means that we can drop God from the equation. At this point, God becomes an idea, perhaps an inspiring thought - this concept fits few notions of God.

In a similar way, saying that God is supernatural would mean that God is unable to interact with the natural world at all, since so far, we have not detected any uncaused action. That is what supernatural would look like, right? Some physical process taking place with no cause acting on it, or through it - like a vase floating from point a to b though the air, with no possible explanation of how it is happening. So at the very least, God inhabits the universe, without simply being the universe. Inhabiting the universe gives the mechanism of action, and not simply being the universe gives the possibility that God is more than another way of saying natural processes.

What about the millions (billions?) of people who say that they have experienced God just that way? A direct-to-brain sense of God speaking to them (figurative or literal), an experience of comfort and assurance, miraculous coincidence, healings, interventions, appearances of angels at just the right time, just the right word from a friend or a stranger, knowledge of the private thoughts of another person, or predictions of future events that turn out just as described? The difficulty is that these experiences don't seem to stand up to scrutiny; that is, they don't seem to have a statistically significant impact on health, longevity, divorce rate, standard of living (if God blesses His own) and so on. Why do we experience significant spiritual events if they don't seem to impact the overall experience of life on earth? For example, Pat Robertson is a world-famous faith healer, yet he is seeking our Western medicine for his prostate cancer. Is it just me, or is this odd? Millions of people are praying for him, yet his disease is progressing in complete accord with statistical norms. Why this disconnect between what we believe, and what seems to be the case?

We don't perceive reality directly (one simple example: objects don't have color, right? Color is literally in the mind - a way we process the eye's reception of various wavelengths of light bouncing off an object - or so we explain it to ourselves). If I read the popular physics books correctly, all of time already exists, and for some reason we don't understand, we are forced to experience it one "slice" at a time, and only in one direction. There are other examples that suggest that we experience only a small subset of what there is, and that experience is heavily structured and mediated (and sometimes even manufactured) by our sensory and cognitive apparatus.

I am not trying to suggest some "gap" in our understanding is where God is. I am trying to suggest that we are heavily invested in our experience of the world, and even things we are confident about (a blue sky day, for example) represent a heavily coded representation of reality, and not reality itself. We pay attention to the things our brain generates based on data from our five senses because that is what we've got. In this sense, we are like the drunk looking for his keys under the streetlight "because the light is better." Our brain looks for patterns (and finds them). Our brain generates explanations for cognitive dissonance (and we believe them, even when they are patently false). We do better with an optimistic outlook, and our brain paints a rosy picture for us (many of us, some of the time).

I don't think that this means we do not know or experience reality (but we are working under some heavy disadvantages). Much of what we know (and we can easily sort truth from fiction here) is grounded in an actual physical system. That we experience those systems at a remove is a truism we skip for the sake of convenience. So to say that the sky is blue is a shorthand way of saying that receptors in our eyes have registered photons in the 475 nm range, and which our brains are mapping as the color blue (or near enough - if the exact process ends up being different, it won't impact this argument). That synesthesia - experiencing color as smell or taste is a clue that this binding is arbitrary (through hard-wired in the brain); but it does not mean that our description of the sky is any less real.

This is one of the reasons that science has been so successful. By challenging assumptions, insisting on data to support ab assertion, carefully running experiments and having others check the results, by having lots of smart people try to disprove an idea (as opposed to apologetics - having those same smart people rationalize why an idea is correct), we are moving in a more "truthlike" direction as regards our understanding of the natural world.

I know that I personally locate the experience of Spirit in my sense of flow, of synchronicity, of connectedness, of things coming together for a purpose. Perhaps I mean grace. I do not understand why so many people's lives appear to lack that grace. The truly wretched state of billions is the strongest argument against grace that I know - and yet, I still believe I experience it, and witness its effects in the world.

Thursday, October 04, 2007

Understanding The World

The best we can do, in our attempt to understand the universe we find ourselves in, is to make models. This is because we do not directly encompass the world with our minds - rather, we store samples of our interactions with the world, and ideas about how the world works and what kind of relationships there are in the world - that is, we make models of the world, and use those models to predict the future and make sense of our circumstances. These models are limited by our ability to reason and remember, and by the tiny subset of data points afforded by our short lifetimes and limited experience. The usefulness of these models is further degraded by the physical limitations of our brain and senses (given to errors in perception, cognition, reasoning and recall).

On top of all of this, we sample our environment at the end of a long chain of events. For example, we experience color as the result of (or at least, so we model it) photons bouncing off of physical objects and entering the structure of our eye, where their energy excites chemical reactions, causing electrical impulses to travel the optic nerve. These signals are then collated into some meaningful pattern which is passed from area to area in our brain. Motion is processed in one area of the brain, pattern-matching occurs somewhere else. At some point in this process, we become aware of these signals as a picture of what is "out there." As you might imagine, there are opportunities all along this chain for failure (no visible light), distortion (optical illusions), and even outright fabrication (hallucinations) to occur.

Rather than give in to Philosophy 101 despair, however, we've adopted any number of mechanisms to compensate for the vagaries of our perceptual apparatus. Someone walks down the street in green pants, and we say to our friend, "Did you see that? "See What?" “Those lime-green pants!” "Sorry, those are not green." Perhaps it is a testament to the unreliability of our senses that we spend so much time calibrating what we experience with those around us. We even tend to surround ourselves with people who experience the world as we do – abandoning the attempt to determine "absolute" truth in favor of a consensus among friends.

All-the-same most of us have a high degree of certainty that what we see is indeed what is out there. Might as well just say it like it is - we are certain that what we see (under a set of fairly broad circumstances) is what is out there, even allowing that we can be wrong, tricked, or from time-to-time confronted with something that we cannot classify or identify. It is the same with our other perceptions, and with our models of the world. Though we may interpret things differently, one person to another, we believe that we can (or could, given enough time and experience) know the “straight facts” about much of the world we live in.

Some philosophers claim that this is not the case. Hume argues, for example, that because many of the inputs for our mental model are mediated by our senses, we can never be certain that what we perceive is really what is "out there." We are doomed to experience the world at a perceptual reserve, never actually coming into contact with the world itself, so always stuck in a “web of guesses.” As a result, the best we can do is to be reasonably certain about our models of reality, and even under the best of circumstances, we must hold open the possibility that we are wrong (maybe there is no sun, it may not appear tomorrow, flipping the light switch may not be what makes the light come on, etc.).

I am not convinced, for a number of reasons.

1. This is a logical problem, which may or may not be connected to reality. In the same way Xeno's Paradoxes "prove" things impossible that we all do every day, Hume's argument may be more about the meaning of words than about our experience of reality. Or to use Xeno's example, if in order to reach an object we must cover half the distance between ourselves and the object, and then half the distance again, and so on, you must come to the logical conclusion that it is not possible to ever actually reach the object. This is logically true, but it does not actually map to our experience of the natural world.

2. We are part of the universe we perceive, not a remote observer. This means that we do not experience reality from outside, but as an observer who is part of the system. This may introduce interesting biases, but it is more reasonable to assume continuity with our surroundings than that we are of a different kind or substance from the world around us. Each part of the system we observe also has this same problem – it is separate from the effects it causes, and from the things that affect it. Yet we can observe that these disconnected things share the same substance, and do indeed supply action and reaction down the chain. We can now even observe our own internal perception processes and follow the causal links (even though we cannot sense these links and processes in the actual acts of perceiving or thinking). In this way, we can confirm that what we are perceiving is indeed the world that is out there.

3. Science, as an extension of the process of verification and validation of our senses that occurs as a normal part of social interaction, acts to confirm and correct our models. As such, we can become certain of some things, even as we withhold judgment on others. Our experience of the world is not uniform, nor is our model uniformly complete (or incomplete). While there are any number of things about which we must hold open the possibility that we are wrong, there is a whole class of things about which we can be certain. For example, while we may not be sure just what gravity is and how it works, we can be certain that when we drop something (within certain well-understood bounds), it falls.

4. Technology has given us extensions to our senses, and external locations for our models and memories. This has resulted in qualitative and quantitative changes in what we know and how we know it. This means that we have overcome some of the objections Hume had about our knowledge and understanding of the world. Our sense impressions and reasonings about the world can be described specifically and unambiguously, and independently checked and verified. For example, a meter measuring stick can be independently manufactured, calibrated, and used to specify the length of an object, which itself can be independently identified and located, resulting in certainty that a particular thing is indeed a specific length (within a pre-defined margin of error). This is certainty. For some parts of our models, it is no longer useful to hold that we cannot be certain – rather, it is now no longer useful to pretend radical skepticism. This is not a universal, but it is non-the-less true.

5. It is just as valid, and much more useful, to suppose that the world is as we experience it as it is to hold open the possibility that it is not as we experience it. Models can always be revised, and assumptions checked – this is standard operating procedure for humans ("Is that what I think it is?"). While it may be an essential part of doing science to hold a skeptical position, it is neither credible nor helpful as a constant (nor does science proceed by holding this kind of skepticism about everything, or every experiment would begin with an infinite recursion of self-doubt). What is more useful is to be able to discriminate between what we are certain about (and the ways in which we are certain), and what we have uncertainty about (and the nature of our uncertainty).

The Nature of Certainty: Science and Faith

Revelation makes two assumptions: a revelation contains information beyond our ability to obtain though natural means, and the revelation can be understood (even if it must be deciphered or interpreted). Because the believer knows the truth (God told them, and is able to directly interface with the brain, bypassing indirect pathways like sight and sound) this belief is immune to Hume's logical objection. If a scientist argues that all knowledge is provisional and might be wrong, the person of faith will take that as an admission that their revelation trumps the scientists’ suppositions (after all, unlike the scientist's knowledge, theirs is certain, and based on "higher" authority, or direct God-to-brain communication). Further, the sacred text is a record of direct-to-brain communication made to trusted individuals in the past, and so also “trumps” mere scientific observation and modeling.

Science argues that it has useful models. These models allow you to make (more) accurate descriptions of behaviors and to make better predictions than many “folk models” arrived at via other methods. They deny certainty, they hold open the possibility that new observations will break their model; even that their models may not correspond to reality, except in some gross, over-simplified way – perhaps more of an analogy or metaphor than a physical description. Even if there is a reality, our brains may not be capable of understanding it, or encompassing it.

Is there an Objective Reality?

Then there is also the post-modern assertion that denies any over-arching explanation that encompasses everyone's experience. Though you can critique from within a narrative, and you can point out logical inconsistencies or examples of how a particular narrative is inconsistent or ineffective, you lack any meta-narrative by which you can make absolute judgments about right and wrong (or even correct and incorrect).

In this sense, post-modernists seem to be taking a page from science; we all have models of the world; they can be more (or less) useful, but we can't know (because we do not experience the world directly) if our models correspond with anything actually “out there.” Language, culture, politics all influence scientific activities and the interpretation of results. For example, Martin Seligman comments about his research on behavior modification that contrary evidence was suppressed, due to the overwhelming sense that BF Skinner was on to something.

Even the suggestion that via experiment and observation (the scientific method) people can arrive at consensus is up for grabs. Due to differences in language and culture (which apparently result in alterations to the shape and function of the brain) two people can reproduce the same experiment and reach different conclusions. Some experiments cannot be reproduced; we can only make observations. From this perspective, we are only left with a kind of pragmatism; what we know works (more-or-less) well; that has to be enough. What you believe is not wrong, it just does not work for me.

Of course, this suggests, not that science cannot discover truth, but that it is a human activity, with all that that implies. In fact, to claim that historical, political, cultural and personal motives and bias influences the models that science generates suggests a path by which those influences can be identified, and perhaps even removed.

I am reminded of Johnson's refutation of Berkely's idealism. Striking his foot on a stone, he said, “I refute it thus!” I am suggesting that our mental models share a material continuum with the stone our toe strikes. We may have to wade through the barriers of differences in brain structure, ways of thinking, differences in perception and analysis, competing models, and social, biological, and political constraints on our science. But in the end, these are things that can be sorted through and compensated for. If we cannot agree on what is, we can at least bound the solution space, and work on ways to further constrain the problem.

On top of all of this, we sample our environment at the end of a long chain of events. For example, we experience color as the result of (or at least, so we model it) photons bouncing off of physical objects and entering the structure of our eye, where their energy excites chemical reactions, causing electrical impulses to travel the optic nerve. These signals are then collated into some meaningful pattern which is passed from area to area in our brain. Motion is processed in one area of the brain, pattern-matching occurs somewhere else. At some point in this process, we become aware of these signals as a picture of what is "out there." As you might imagine, there are opportunities all along this chain for failure (no visible light), distortion (optical illusions), and even outright fabrication (hallucinations) to occur.

Rather than give in to Philosophy 101 despair, however, we've adopted any number of mechanisms to compensate for the vagaries of our perceptual apparatus. Someone walks down the street in green pants, and we say to our friend, "Did you see that? "See What?" “Those lime-green pants!” "Sorry, those are not green." Perhaps it is a testament to the unreliability of our senses that we spend so much time calibrating what we experience with those around us. We even tend to surround ourselves with people who experience the world as we do – abandoning the attempt to determine "absolute" truth in favor of a consensus among friends.

All-the-same most of us have a high degree of certainty that what we see is indeed what is out there. Might as well just say it like it is - we are certain that what we see (under a set of fairly broad circumstances) is what is out there, even allowing that we can be wrong, tricked, or from time-to-time confronted with something that we cannot classify or identify. It is the same with our other perceptions, and with our models of the world. Though we may interpret things differently, one person to another, we believe that we can (or could, given enough time and experience) know the “straight facts” about much of the world we live in.

Some philosophers claim that this is not the case. Hume argues, for example, that because many of the inputs for our mental model are mediated by our senses, we can never be certain that what we perceive is really what is "out there." We are doomed to experience the world at a perceptual reserve, never actually coming into contact with the world itself, so always stuck in a “web of guesses.” As a result, the best we can do is to be reasonably certain about our models of reality, and even under the best of circumstances, we must hold open the possibility that we are wrong (maybe there is no sun, it may not appear tomorrow, flipping the light switch may not be what makes the light come on, etc.).

I am not convinced, for a number of reasons.

1. This is a logical problem, which may or may not be connected to reality. In the same way Xeno's Paradoxes "prove" things impossible that we all do every day, Hume's argument may be more about the meaning of words than about our experience of reality. Or to use Xeno's example, if in order to reach an object we must cover half the distance between ourselves and the object, and then half the distance again, and so on, you must come to the logical conclusion that it is not possible to ever actually reach the object. This is logically true, but it does not actually map to our experience of the natural world.

2. We are part of the universe we perceive, not a remote observer. This means that we do not experience reality from outside, but as an observer who is part of the system. This may introduce interesting biases, but it is more reasonable to assume continuity with our surroundings than that we are of a different kind or substance from the world around us. Each part of the system we observe also has this same problem – it is separate from the effects it causes, and from the things that affect it. Yet we can observe that these disconnected things share the same substance, and do indeed supply action and reaction down the chain. We can now even observe our own internal perception processes and follow the causal links (even though we cannot sense these links and processes in the actual acts of perceiving or thinking). In this way, we can confirm that what we are perceiving is indeed the world that is out there.

3. Science, as an extension of the process of verification and validation of our senses that occurs as a normal part of social interaction, acts to confirm and correct our models. As such, we can become certain of some things, even as we withhold judgment on others. Our experience of the world is not uniform, nor is our model uniformly complete (or incomplete). While there are any number of things about which we must hold open the possibility that we are wrong, there is a whole class of things about which we can be certain. For example, while we may not be sure just what gravity is and how it works, we can be certain that when we drop something (within certain well-understood bounds), it falls.

4. Technology has given us extensions to our senses, and external locations for our models and memories. This has resulted in qualitative and quantitative changes in what we know and how we know it. This means that we have overcome some of the objections Hume had about our knowledge and understanding of the world. Our sense impressions and reasonings about the world can be described specifically and unambiguously, and independently checked and verified. For example, a meter measuring stick can be independently manufactured, calibrated, and used to specify the length of an object, which itself can be independently identified and located, resulting in certainty that a particular thing is indeed a specific length (within a pre-defined margin of error). This is certainty. For some parts of our models, it is no longer useful to hold that we cannot be certain – rather, it is now no longer useful to pretend radical skepticism. This is not a universal, but it is non-the-less true.

5. It is just as valid, and much more useful, to suppose that the world is as we experience it as it is to hold open the possibility that it is not as we experience it. Models can always be revised, and assumptions checked – this is standard operating procedure for humans ("Is that what I think it is?"). While it may be an essential part of doing science to hold a skeptical position, it is neither credible nor helpful as a constant (nor does science proceed by holding this kind of skepticism about everything, or every experiment would begin with an infinite recursion of self-doubt). What is more useful is to be able to discriminate between what we are certain about (and the ways in which we are certain), and what we have uncertainty about (and the nature of our uncertainty).

The Nature of Certainty: Science and Faith

Revelation makes two assumptions: a revelation contains information beyond our ability to obtain though natural means, and the revelation can be understood (even if it must be deciphered or interpreted). Because the believer knows the truth (God told them, and is able to directly interface with the brain, bypassing indirect pathways like sight and sound) this belief is immune to Hume's logical objection. If a scientist argues that all knowledge is provisional and might be wrong, the person of faith will take that as an admission that their revelation trumps the scientists’ suppositions (after all, unlike the scientist's knowledge, theirs is certain, and based on "higher" authority, or direct God-to-brain communication). Further, the sacred text is a record of direct-to-brain communication made to trusted individuals in the past, and so also “trumps” mere scientific observation and modeling.

Science argues that it has useful models. These models allow you to make (more) accurate descriptions of behaviors and to make better predictions than many “folk models” arrived at via other methods. They deny certainty, they hold open the possibility that new observations will break their model; even that their models may not correspond to reality, except in some gross, over-simplified way – perhaps more of an analogy or metaphor than a physical description. Even if there is a reality, our brains may not be capable of understanding it, or encompassing it.

Is there an Objective Reality?

Then there is also the post-modern assertion that denies any over-arching explanation that encompasses everyone's experience. Though you can critique from within a narrative, and you can point out logical inconsistencies or examples of how a particular narrative is inconsistent or ineffective, you lack any meta-narrative by which you can make absolute judgments about right and wrong (or even correct and incorrect).

In this sense, post-modernists seem to be taking a page from science; we all have models of the world; they can be more (or less) useful, but we can't know (because we do not experience the world directly) if our models correspond with anything actually “out there.” Language, culture, politics all influence scientific activities and the interpretation of results. For example, Martin Seligman comments about his research on behavior modification that contrary evidence was suppressed, due to the overwhelming sense that BF Skinner was on to something.

Even the suggestion that via experiment and observation (the scientific method) people can arrive at consensus is up for grabs. Due to differences in language and culture (which apparently result in alterations to the shape and function of the brain) two people can reproduce the same experiment and reach different conclusions. Some experiments cannot be reproduced; we can only make observations. From this perspective, we are only left with a kind of pragmatism; what we know works (more-or-less) well; that has to be enough. What you believe is not wrong, it just does not work for me.

Of course, this suggests, not that science cannot discover truth, but that it is a human activity, with all that that implies. In fact, to claim that historical, political, cultural and personal motives and bias influences the models that science generates suggests a path by which those influences can be identified, and perhaps even removed.

I am reminded of Johnson's refutation of Berkely's idealism. Striking his foot on a stone, he said, “I refute it thus!” I am suggesting that our mental models share a material continuum with the stone our toe strikes. We may have to wade through the barriers of differences in brain structure, ways of thinking, differences in perception and analysis, competing models, and social, biological, and political constraints on our science. But in the end, these are things that can be sorted through and compensated for. If we cannot agree on what is, we can at least bound the solution space, and work on ways to further constrain the problem.

Tuesday, October 02, 2007

Is This What It Means to Be Post-Modern?

If by postmodern, we mean that "meta-narratives" (a coherent, all-encompassing story that gives shape and meaning to our lives) like science and ideologies (-isms and -itys of all sorts) have failed us (or are just not all-encompassing enough), then maybe the post-modernest has (quite unconsciously) decided to inhabit adjacent "pools" of perspective. In one environment, and with one community, perhaps we accept cause-and-effect, and look toward the rational and scientific for guidance. Later, with other folks, or while immersed in other objectives, we are intuitive, or non-rational (even mystical)- and embrace ideas no science can prove. Rather than try to tie the two together, perhaps we simply put these meta-narratives on and off as required.

Our desire for a story, a direction, a purpose to our lives may be more important to us than any sort of literal or scientific truth. Our comfort and survival may be more important than any ideology or religion. Our language, our brain, our limited experience may condemn us to a partial, unsatisfactory understanding of whatever it is we turn our minds to. We fill in the sketchy parts with a story, or some speculation, or even rationalization.

We may be willing (even eager) to discover lacuna (gaps in our meta-narratives, which are then available to fill with our own conjecture) into which we place our sense of significance (isn't this what the mystification of Quantum Mechanics is all about? Expanding the interactions of the unimaginably small to hold our hopes and dreams, to keep them safe from the relentlessly Newtonian universe that rules at our scale of existence)?

Even knowing that soul and spirit are not different from the brain and body (or perhaps they turn out to be epi-physical; latent, but actually generated by interactions between our brain and our environment - family, community and language (and so tied to our zeitgeist), manifesting in physical changes to our brain), won't we continue to experience pattern, and significance, and intuition; to experience life as larger than our ability to comprehend it (even if this is "simply" a limitation of our brain) - precisely so that there is some place for hope, and dream and destination?

Our desire for a story, a direction, a purpose to our lives may be more important to us than any sort of literal or scientific truth. Our comfort and survival may be more important than any ideology or religion. Our language, our brain, our limited experience may condemn us to a partial, unsatisfactory understanding of whatever it is we turn our minds to. We fill in the sketchy parts with a story, or some speculation, or even rationalization.

We may be willing (even eager) to discover lacuna (gaps in our meta-narratives, which are then available to fill with our own conjecture) into which we place our sense of significance (isn't this what the mystification of Quantum Mechanics is all about? Expanding the interactions of the unimaginably small to hold our hopes and dreams, to keep them safe from the relentlessly Newtonian universe that rules at our scale of existence)?

Even knowing that soul and spirit are not different from the brain and body (or perhaps they turn out to be epi-physical; latent, but actually generated by interactions between our brain and our environment - family, community and language (and so tied to our zeitgeist), manifesting in physical changes to our brain), won't we continue to experience pattern, and significance, and intuition; to experience life as larger than our ability to comprehend it (even if this is "simply" a limitation of our brain) - precisely so that there is some place for hope, and dream and destination?

Saturday, September 29, 2007

Secularism is Not Secular Humanism

Secularism is an approach to civil order that argues that the religious beliefs of a particular sect or religion should not dominate the legal and social structures of a society. It is an approach to dealing with pluralism. What do you do when the citizens of your country are not just biblical literalists, but also Protestants with varying views of the Bible; Catholics, Orthodox, Gnostic and so on (yes, including mutually contradictory beliefs on what constitutes heresy), not to mention Mormonism, Scientology, Unity, various Native American, Pagan, Islamic, Hindu, Buddhist, Janist, Zoroastrian, etc. etc.?

One approach is to set up religious police (dare I say Inquisitor?). You can revise the Constitution to include a religious test for public office (surely if teachers have to pass muster on what they can teach, politicians should as well). Of course, I hope you will agree that this is not a good idea (if for no other reason than there is insufficient time for any particular group to vet everyone, and you really can't trust anyone else, if the history of denominational splits is any indication). After all, without a national religious purity group, you'd get all sorts of regional and local variation, and that won't do, if the point is adherence to a particular approach to biblical literalism. Sure, conservative are banded together now, but that is because of a perceived common enemy. There would be no where near as much cooperation in victory.

The alternative is to remain a secular state. So what does that mean? It means that you don't push ANYONE's religion. So what do you teach in school? Reading, writing, math, science, the arts, history, humanities...

Of course, you immediately run afoul of various faiths at this point. What books do you read? Whose history do you teach? What is a fitting subject of the arts? What views can be expressed, especially if they are critical of a particular religious belief or practice? What conclusions of science do you discuss? Almost all scientific facts offend someone's religious beliefs. Christian Scientists reject the germ theory of disease. Mormons dispute the settlement patterns of North America, Hindus reject the idea of the heat death of the universe, Islamic, Christian, Jewish and Hindu conservatives reject evolution (though they may disagree on the details of the alternatives).

If you are a biblical literalist, do you think about these questions - the implications of the cultural victory you strive for, or do you long for a theistic state, with your interpretation of the Bible deciding all these questions, forgetting the struggle for power that comes with control of the apparatus of government? Can you see that even if you want a theocracy, you have no consensus on how that works out in practice? That the history of religious / state conflicts have been bloody and savage? That our Constitution enshrines secularism for a reason? If you are not a literalist, do you see that this discussion is important, perhaps even critical?

I do not want biblical literalists to force my children to learn a non-scientific, non-biblical version of history and science. I don't want to live in fear of being punished because I have run afoul of one specific group's religious beliefs about the fitness of my faith to pastor a church or teach in public school. I hold that it is wrong to force a particular religion on the culture, and to fire teachers who have done no more than state what the evidence demonstrates; that the creation story and the flood are non-historical; that evolution best explains the diversity of life on the planet; that God speaks through people, who share the cultural limitations of their place in history. Sure, you can believe as you see fit; but the broader culture should not be forced to live under your censorship, especially when it comes to the discoveries of science.

One approach is to set up religious police (dare I say Inquisitor?). You can revise the Constitution to include a religious test for public office (surely if teachers have to pass muster on what they can teach, politicians should as well). Of course, I hope you will agree that this is not a good idea (if for no other reason than there is insufficient time for any particular group to vet everyone, and you really can't trust anyone else, if the history of denominational splits is any indication). After all, without a national religious purity group, you'd get all sorts of regional and local variation, and that won't do, if the point is adherence to a particular approach to biblical literalism. Sure, conservative are banded together now, but that is because of a perceived common enemy. There would be no where near as much cooperation in victory.

The alternative is to remain a secular state. So what does that mean? It means that you don't push ANYONE's religion. So what do you teach in school? Reading, writing, math, science, the arts, history, humanities...

Of course, you immediately run afoul of various faiths at this point. What books do you read? Whose history do you teach? What is a fitting subject of the arts? What views can be expressed, especially if they are critical of a particular religious belief or practice? What conclusions of science do you discuss? Almost all scientific facts offend someone's religious beliefs. Christian Scientists reject the germ theory of disease. Mormons dispute the settlement patterns of North America, Hindus reject the idea of the heat death of the universe, Islamic, Christian, Jewish and Hindu conservatives reject evolution (though they may disagree on the details of the alternatives).

If you are a biblical literalist, do you think about these questions - the implications of the cultural victory you strive for, or do you long for a theistic state, with your interpretation of the Bible deciding all these questions, forgetting the struggle for power that comes with control of the apparatus of government? Can you see that even if you want a theocracy, you have no consensus on how that works out in practice? That the history of religious / state conflicts have been bloody and savage? That our Constitution enshrines secularism for a reason? If you are not a literalist, do you see that this discussion is important, perhaps even critical?

I do not want biblical literalists to force my children to learn a non-scientific, non-biblical version of history and science. I don't want to live in fear of being punished because I have run afoul of one specific group's religious beliefs about the fitness of my faith to pastor a church or teach in public school. I hold that it is wrong to force a particular religion on the culture, and to fire teachers who have done no more than state what the evidence demonstrates; that the creation story and the flood are non-historical; that evolution best explains the diversity of life on the planet; that God speaks through people, who share the cultural limitations of their place in history. Sure, you can believe as you see fit; but the broader culture should not be forced to live under your censorship, especially when it comes to the discoveries of science.

Thursday, September 20, 2007

Why Are Some Christians so Wedded to Creationism?

After some years of trying (with little success) to convince creationists that the evidence for evolution is overwhelming, it has become clear that the objection is primarily theological, and not evidential. The reason that creationists will not accept evolution is because it contradicts their theology, and no amount of reasoning concerning evolution will address that.

This leads me to the conclusion that more attention needs to be placed on the theology of creationism. There are at least two faulty assumptions creationists make. First, that the Bible should be taken as “literal” truth, and second, that the God of the Bible would deceive humans (plant misleading evidence) as to the origins of the natural world by making it seem that the world is one way (old), while it is actually some other way (young).

Assumption 1: The Bible is Meant to Be Taken Literally

Creationists argue that the main mode for understanding the Bible is to take its plain meaning. Though this is a generally sound approach, it fails when you ignore the cultural and historical context of the Bible, and when you ignore clues from the natural world. For example, creationists argue that the Genesis creation accounts are to be taken literally. There are several problems with this assertion.

1. Both Jewish and Christian theologians, both today and throughout history, have taken a variety of non-literal views of the Genesis story. Though a literal approach is one possibility, given scientific evidence, it should be abandoned, just as the church abandoned geocentrism.

2. There are two creation stories (Genesis 1:1-2:3, and Genesis 2:4-2:25). These accounts do not mesh, leading to the clear conclusion that neither should be viewed as “scientific” truth about how the world came to be, and how life (and people) were created. The most obvious demonstration of the need for a non-literal approach here is that that man and woman are created together, in the image of God, and after plants and animals in the first story, while man is created BEFORE plants, animals, sun, moon and stars in the second story, with woman created almost as an afterthought (“but for the man, no suitable helper could be found”) from man‘s rib.

3. The Genesis creation story does not make sense as a scientific explanation, as day and night are “created” before the sun, green plants before the sun, and the sun, moon and stars all described as being fixed in the sky.

4. Stories like the long day in Joshua 10 (which states in verse 11 “The sun stopped in the middle of the sky and delayed going down about a full day“) show that the Bible incorporates then-current cosmology into its worldview (we know this, because stopping the sun would not impact the length of the day).

5. Stories like Noah’s ark (which describe a worldwide flood that did not happen) reinforce that the Bible is not a science textbook. Apologetics for the global flood end up making claims that the Bible itself does not support (for example, large-scale geographic changes - gorges carved, mountains raised etc).

Assumption 2: Scientific Evidence is Wrong (God Intended Non-Believers to be Deceived)

Creationists have to deny that science discovers accurate things about the world. Taken as a whole, there is no doubt that the world is old, and that we share common ancestors with all life. There is no evidence for a young earth or special creation. These facts have to be denied, in order to promote creationism. Science is not judged by how closely it describes reality, but by how close it matches creationism. "Useful" science is readily incorporated into creationist doctrine (for example, "micro" evolution), but those same scientists are suspect when they fail to support creationist theology.

1. While accusing scientists of fabricating support for evolution, creationists distort the plain meaning of the Bible, create miracles where none are mentioned (parent-less baby dinosaurs living as vegetarians on the ark), and believe things about evolution and biology that no working scientist finds credible (for example, the extinction of dinosaurs in rigid order (all the dinosaurs of the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous dying in the same group order all over the world, without EVER getting mixed up). Easy to explain if they were separated by millions of years - rather more difficult if they all lived at the same time only a few thousand years ago).

2. Creationists Arbitrarily Deny "Macro" Evolution

Just like creationists had to admit that the “geocentric” view of the Bible was wrong, so they have had to concede that evolution, as a mechanism, exists (after all, we observe it real-time in the lab, and in the world around us). So now they accept “micro” evolution (changes within species), but deny the evolution of major organs or systems (in spite of excellent evidence for the evolution of flight three different times, or the land-mammal-to-whale fossil evidence - to mention just two examples among many). Why deny "macro" evolution? Because they have had to fabricate an extra-biblical concept of "kinds" as generic animals types from which modern animals evolved in order to maintain a belief in special creation.

3. Creationists Arbitrarily Endow "Micro" Evolution with Abilities it Lacks

Now that they have embraced evolution, they credit it with far more than can be supported by the evidence or theory. From a few thousand “kinds“ on the ark, more than 16 million plus species must have radiated out from Mount Ararat to all the remote corners of the world - crossing oceans, adapting to new environments, evading new predators. And remember that we have written history going back to the supposed flood date, and the existing species we are familiar with were with us then as well, so this must have happened in the blink of an eye. If the flood happened around 2500 B.C., this gives virtually no time for this incredibly rapid evolution. Again, no scientist believes that the genome is capable of this rate of evolution, nor is there any explanation for why the rate of evolution ground to a halt some four thousand years ago.

A Powerful Motivation

So creationists are in the uncomfortable position of forcing the Bible to mean things it clearly does not, and forcing evolution to do things it clearly cannot. There must be a powerful motivation for this kind of rationalization and denial. I think there are at least 4:

1. A Desire to Control the Interpretation of the Bible

The larger church has embraced a wide range of Biblical interpretation. Creationists are uncomfortable with many of these, and see Biblical literalism as a way of “closing the door” on teachings they do not approve of (while reserving the right to interpret the Bible less literally when needed (for example, in “harmonizing” Genesis 1 and 2, or allowing women to go to church with heads uncovered)).

2. A Desire to Retain Confidence in the Historicity of the Bible